From The Virginian-Pilot By Sean Kennedy

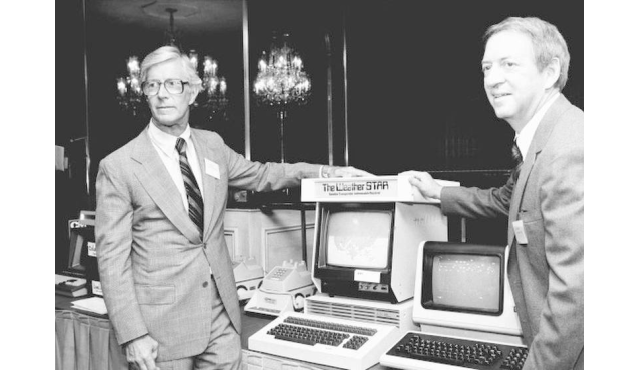

In this July 30, 1981 photo, John Coleman, weather channel founder, right, and Frank Batten, publisher of the Norfolk Virginian-Pilot and Ledger-Star, and chairman and chief executive of Landmark Communications, Inc., are seen during a news conference in New York.

In 1982, Virginian-Pilot publisher and Landmark Communications executive Frank Batten bet big that people around the country wanted — needed — weather news around the clock.

He was right.

On May 2nd, 40 years ago, Batten pushed a button and launched The Weather Channel.

Below is a story that appeared in The Virginian-Pilot and the Ledger Star on May 2, 1982, by longtime Pilot reporter Larry Bonko:

Cable hails 24-hour weather

By Larry Bonko

Published Sunday, May 2, 1982

ATLANTA — When meteorologist John Coleman first worked on television 29 years ago, he delivered 18 minutes of weather every day to the people watching WCIA-TV in his hometown of Champaign, Ill.

A miserly 18 minutes of weather forecasting in a 24-hour day.

Not enough, Coleman told his superiors in Champaign.

Later in Peoria, Omaha, Milwaukee, Chicago, and on the ABC network with “Good Morning, America,” Coleman said it again and again. “Give me more time for the weather, please.”

Coleman stops begging tonight.

The kid with the sweet tooth finally has a candy store of his own. Starting at 8:30, meteorologist Coleman gets his very own channel. Twenty-four hours of live weather, seven days a week on cable television.

Coleman is president, part-owner, super salesman, founder, head cheerleader, and guiding light of The Weather Channel. He will be in Las Vegas tonight, on the eve of the National Cable Association’s annual convention, as Frank Batten pushes the button to sign on The Weather Channel.

Batten is chairman of the board of Landmark Communications, the Norfolk company which publishes The Virginian-Pilot and The Ledger-Star newspapers and which is betting $25 million on Coleman’s hunch that America wants and needs an uninterrupted flow of live weather forecasts on cable television.

Landmark’s cable television subsidiary, TeleCable Corp., owns 20 cable systems with 315,000 subscribers in 15 states — the nation’s 14th largest cable system.

“If The Weather Channel lays an egg, I will feel rotten. But it won’t lay an egg. It’s gonna do terrific,” Coleman said here before flying off to Las Vegas to help Batten launch TV’s first round-the-clock weather programming.

The 86,000 customers of Cox Cable in Tidewater will have The Weather Channel in their basic cable package of $7.50. But not until on or about June 1.

Even without Tidewater’s subscribers, The Weather Channel will be available to 4.1 million homes wired for cable from Portland, Me., to Portland, Ore., from Miami, Fla., to Anaheim, Calif. No other cable network — not all-news, not all-sports — had such a vast audience at the start.

“There are weather junkies as there are news and sports junkies,” Coleman said. “I’m well aware of the skeptics. But believe me, there is a passionate need to know more about the weather out there.

“I think we have something hypnotic, seductive in The Weather Channel.”

Coleman expects the average viewer to take The Weather Channel in 15- to 20-minute doses. According to Coleman, television is the principal source of weather information for 77 percent of the population.

In 11 months here in leafy old Atlanta, Coleman brought together 120 people. These weather specialists have been working with seven fully independent computer systems (an eighth is on the way), transmissions from four weather satellites and sightings of 80 radar stations in the outpouring of the National Weather Service computer near Washington, D.C. Flesh and machine come together on the second floor of an office building not far from where Sherman paused in his march through Georgia and pitched camp in 1864.

From 2840 Mount Wilkinson Parkway in northwest Atlanta, The Weather Channel’s signal flies across fiber-optic cables no bigger around than a human hair to machinery (uplink, they call it in the cable business) which relays the pictures to an RCA Satcom III-R satellite. Landmark paid $10.5 million last July for a transponder lease on that satellite 22,300 miles up.

Starting tonight, that satellite will be cable subscribers’ window to weather, with reporting day and night by 27 meteorologists in three-piece suits —including John Hope, 41 years a U.S. government forecaster, formerly the National Weather Service’s No. 1 hurricane hunter in Miami. Coleman, the $250,000-a-year talent with “Good Morning, America,” will begin appearing on The Weather Channel In September. Meanwhile, he’s working behind the scenes 13 hours a day, chain-smoking and drinking eight to 10 Tabs a day.

His contract with ABC-TV has 28 months to run, so you’ll still see him on “Good Morning, America” well into 1984. Whether he stays with the morning show after that is questionable.

Coleman moved from Chicago to nearby Roswell, Ga., last winter and since then he has been doing the weather for “Good Morning, America” from an ABC affiliate, WSB-TV, here. From now on, the staff at The Weather Channel will supply Coleman with all his pictures, charts, and forecasts.

Coleman begins his day at 3:30 a.m. and continues to work long after the supper hour.

ABC-TV believes that a few moments of weather is enough in the “Good Morning, America” program. Now here come Coleman and his colleagues with weather that never stops — hours and hours of highs, lows, thunderstorm watches, tornadoes on radar, pre-briefing for pilots, and a lot more in living color. Believe it or not, it all works.

The Weather Channel is entertainment. The pace is quick. The tempo is upbeat.

Coleman’s people have been on a shakedown cruise here since April 5. They are getting very good at this. Two meteorologists at a time stand before the cameras in 30-minute shifts, tracking the weather in all corners of the United States, showing the storms in colors as vivid as those on Monet’s palette. The TV screen explodes with words and pictures, zooming in on a severe thunderstorm watch in southeast Georgia from 2:32 p.m. to 8:30 p.m., or a nasty storm off Hatteras pushing toward Norfolk.

This is the national weather picture in reds, browns, greens and blues.

And once every five minutes on The Weather Channel, they present the local forecast.

When it’s time for the local segments, the two meteorologists on duty fade out of the picture and up pops the forecast for your town In words and numbers. Yours to read.

“We give the highest priority to this forecast,” Coleman said. “In 29 years of doing weather on television, I’ve teamed that the best way to do local weather is to write it out on the screen. At The Weather Channel, we’ll put music with the local forecast. That makes it entertaining.”

In a typical hour on The Weather Channel, you are likely to see traveler’s weather, a report from the ski resorts in season, weather that fishermen will be interested in, a view of the eastern United States from one of the satellites, city-by-city temperatures, one-minute features such as the American Almanac (heatwave in January, snow in July) and commercials. Yes, advertisers will pay the freight rate on The Weather Channel. But the commercials and features are never longer than 60 seconds, so you are never more than a minute away from the weather.

The local forecast, bulletins and weather up dates show up on your TV screen because The Weather Channel has sent to your cable system the Satellite Transponder Addressable Receiver (STAR). It is a box about the sire of a kitchen drawer through which 1be Weather Channel meteorologists send or address local weather in an instant — high-speed Teltext. The STAR is a $6,000 machine which wasn’t even invented a year ago.

Local forecasting is the No. 1 priority of The Weather Channel. Without the STAR, there would be no instant local weather. “Last year, when the ink was still wet on the contract I signed with Landmark, I said let’s build this thing, the STAR,’’ Coleman said.

ComPuVid of Utah built the STAR with help from people like Alan Galumbeck, Duane Fetters, Nick Worth and Gordon Herring, all from Landmark divisions in Norfolk. Hugh M. Eaton Jr., from Virginia Beach, is now vice president and general manager of The Weather Channel. Doyle Thompson left Tidewater to become director of engineering.

The technology one sees here in The Weather Channel’s meteorology laboratory, anchor studio, master control, computer rooms, twin-digital radar receivers and imagery from the geo-stationary satellite (a word only an engineer could love) is dazzling. Reports of weather around the world can be summoned in an Instant and displayed on TV screens here. Where is the weather lousy? Treacherous?

Punch a key and you find out in an instant that Nantucket has fog or Charlottesville, Va. is having heavy rain.

Beautiful.

But The Weather Channel is more than just a pretty picture, Coleman reminds any visitor to the studios here. “Weather is important in so many ways involving personal safety — tornadoes, hurricanes, floods, droughts, extreme cold, blizzards, extreme heat. Do you know how many people died as a direct or indirect result of last year’s heatwave? 12,000. 12,000!”

Batten is in Las Vegas today predicting that his Weather Channel will be a great big hit on cable television. “There are few things as vital to people’s lives that change as fast as the weather. We think that The Weather Channel, with its live continuous weathercast, will be the most-watched channel on cable television.”

Weather junkies rejoice. Your day has come.